The Road to

Book-based Mapbox style

following the steps of Bill Bryson

following the steps of Bill Bryson

09-12-2024

to

The Road

Book-based Mapbox style

following the steps

of Bill Bryson

following the steps

of Bill Bryson

09-12-2024

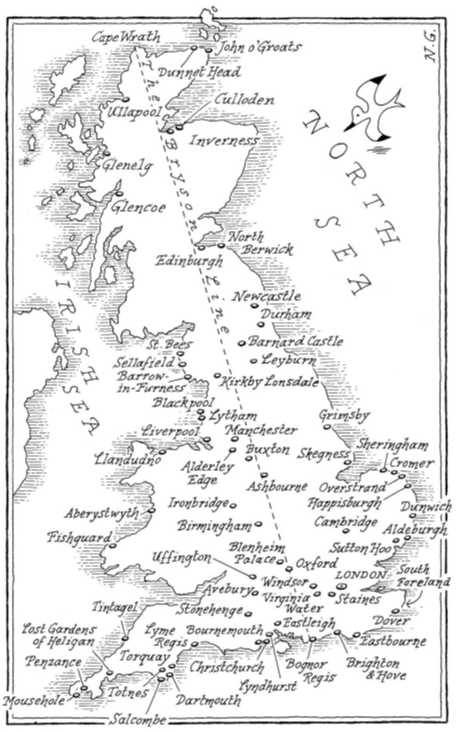

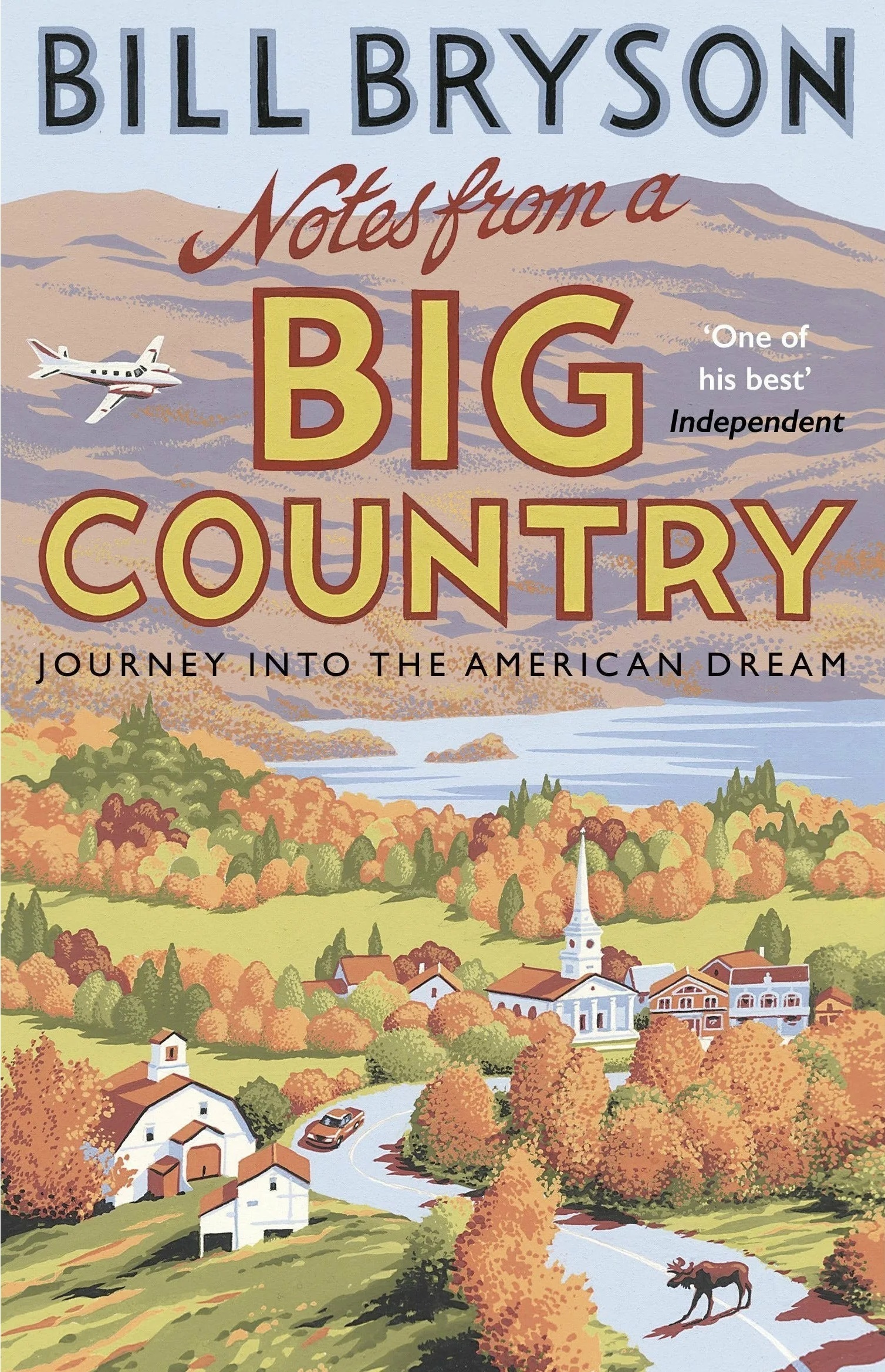

I’ve long been a huge fan of Bill Bryson’s travel writing. My bookish interests in general often find their way into cartographic projects and, even though The Road to Little Dribbling is by far not my favourite Bryson’s book, its British setting became an occasion for this mapping experiment.

The book already has a map: Bryson starts it up with an intention to cross over Britain through a straight line from Bognor Regis to Cape Wrath (‘Bryson Line’). However, since the very beginning he generously includes within the buffer of its line places within a couple of hundred miles on either side of it - say, the whole Britain.

The book already has a map: Bryson starts it up with an intention to cross over Britain through a straight line from Bognor Regis to Cape Wrath (‘Bryson Line’). However, since the very beginning he generously includes within the buffer of its line places within a couple of hundred miles on either side of it - say, the whole Britain.

Before I went there for the first time, about all I knew about Bognor Regis, beyond how to spell it, was that some British monarch, at some uncertain point in the past, in a moment of deathbed acerbity, called out the words ‘Bugger Bognor’ just before expiring, though which monarch it was and why his parting wish on earth was to see a medium-sized English coastal resort sodomised are questions I could not answer.

Bryson in 'The road to Little Dribbling'

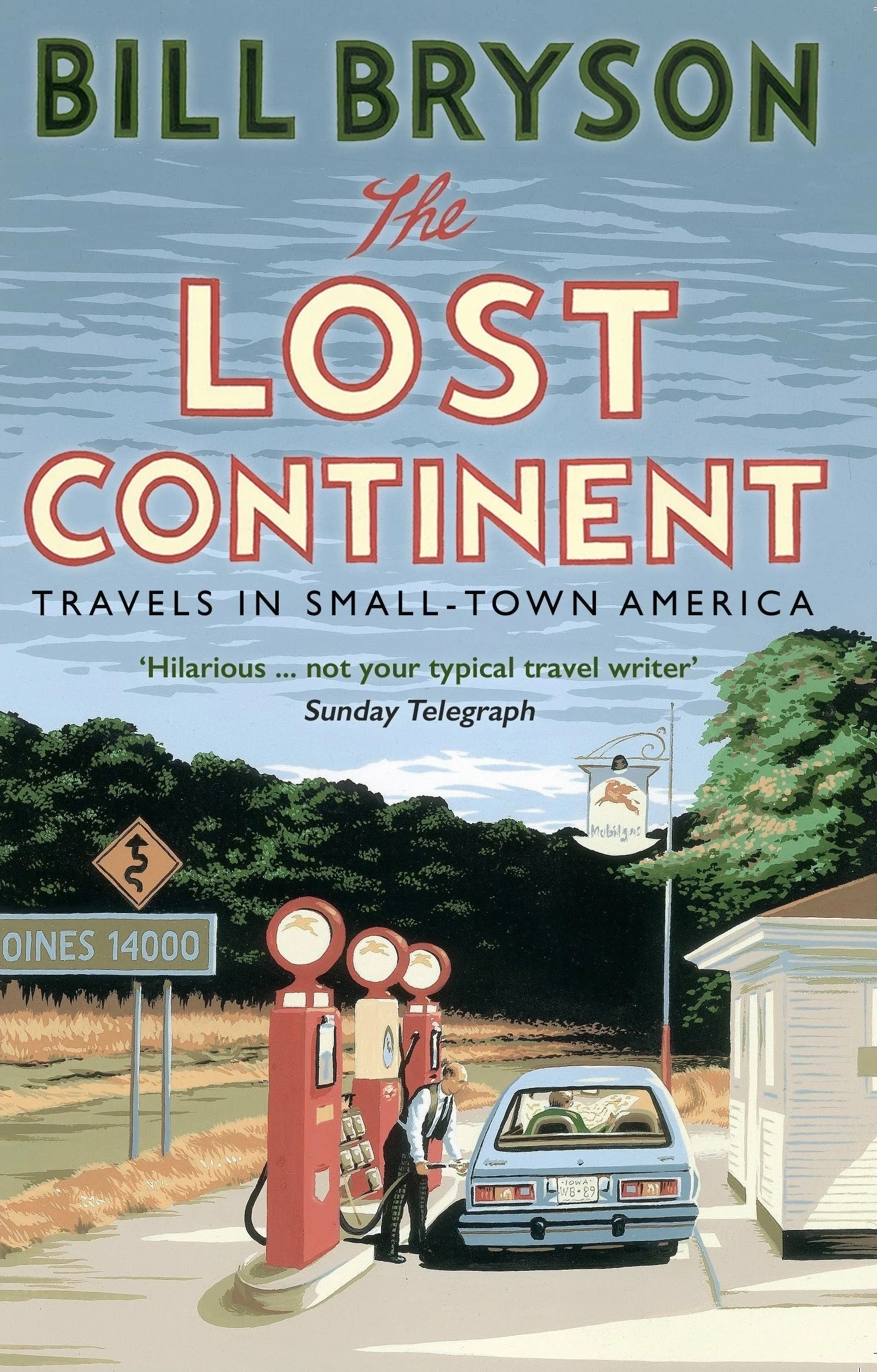

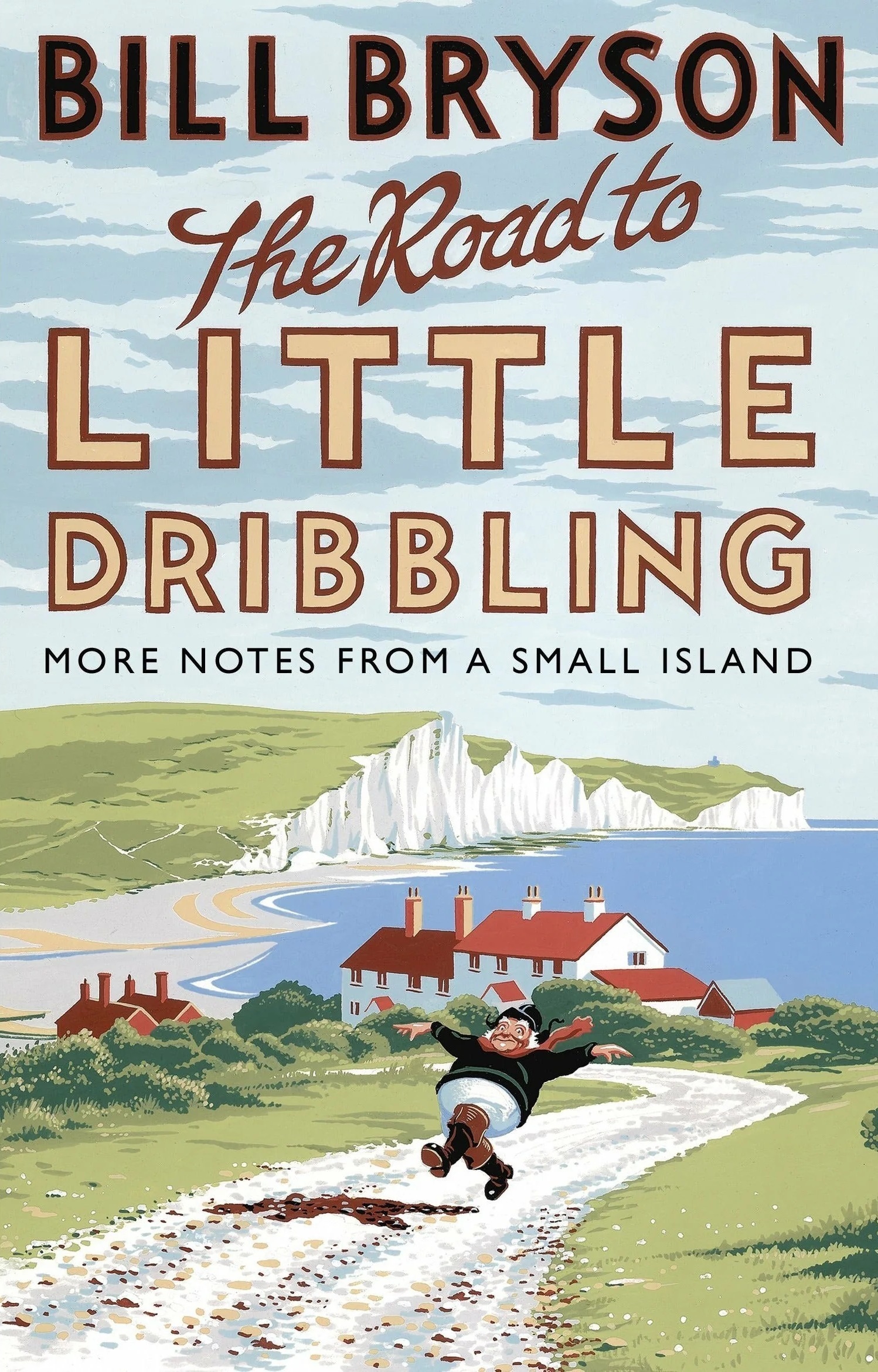

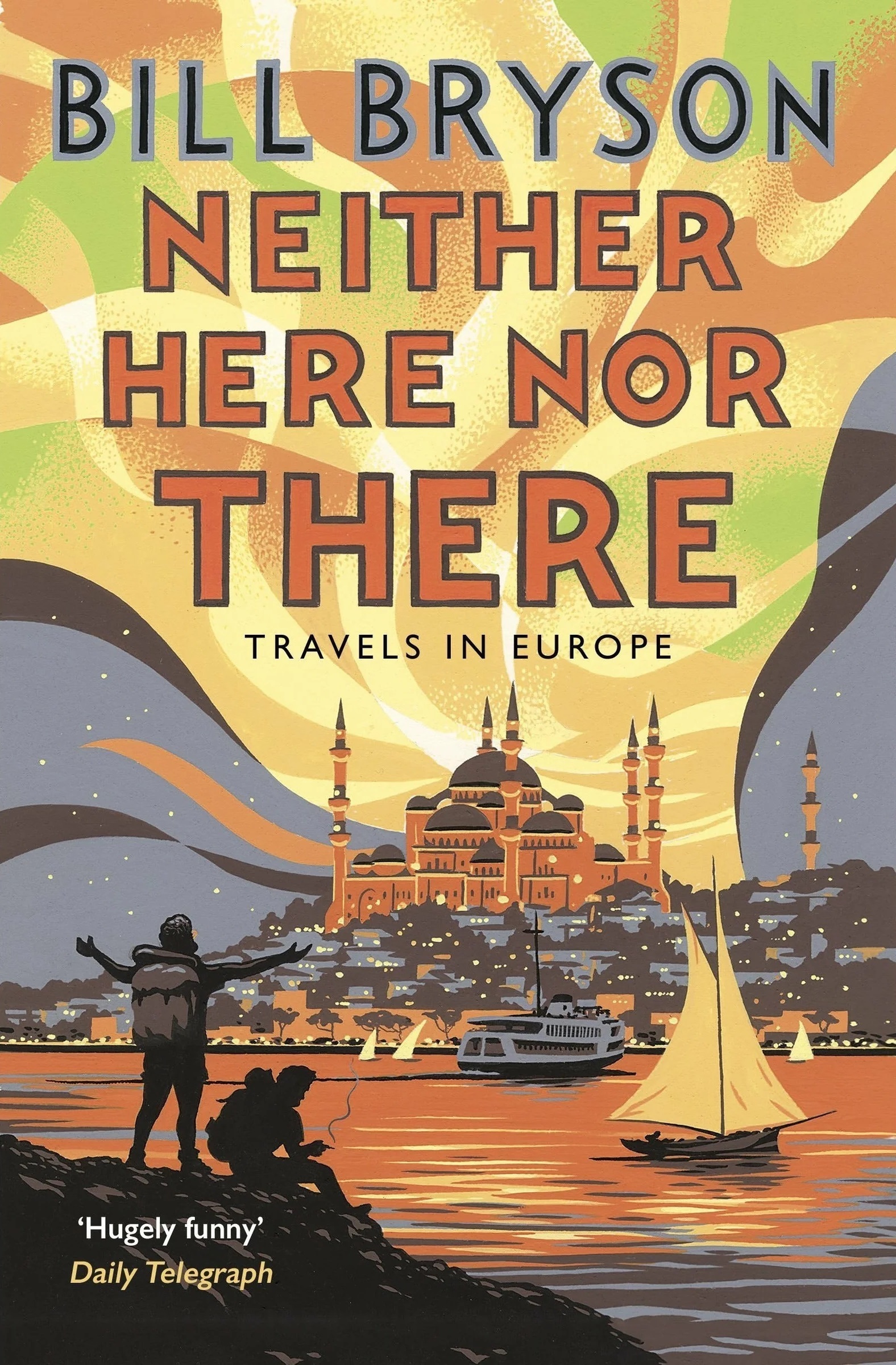

I have to admit that I’m someone who often chooses a book by its cover. In this case, I’m familiar with both the author and his books, but this particular Black Swan edition has absolutely wonderful covers. As far as I can tell, they themselves are inspired by the American poster design from the 1930s:

Bryson in 'The road to Little Dribbling'

I have to admit that I’m someone who often chooses a book by its cover. In this case, I’m familiar with both the author and his books, but this particular Black Swan edition has absolutely wonderful covers. As far as I can tell, they themselves are inspired by the American poster design from the 1930s:

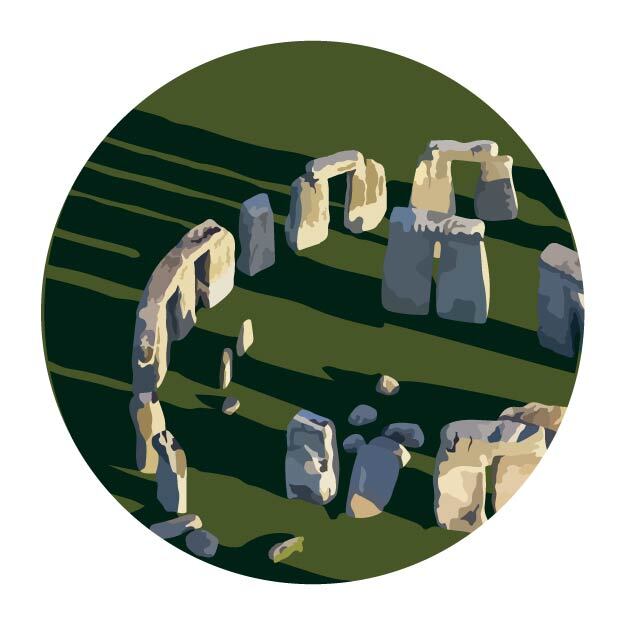

Referring to these designs, I started out with digitally drawing a set of icons for some of the locations mentioned in the book. They are meant to be visually linked between the book cover design and the basemap (at that time non-existent):

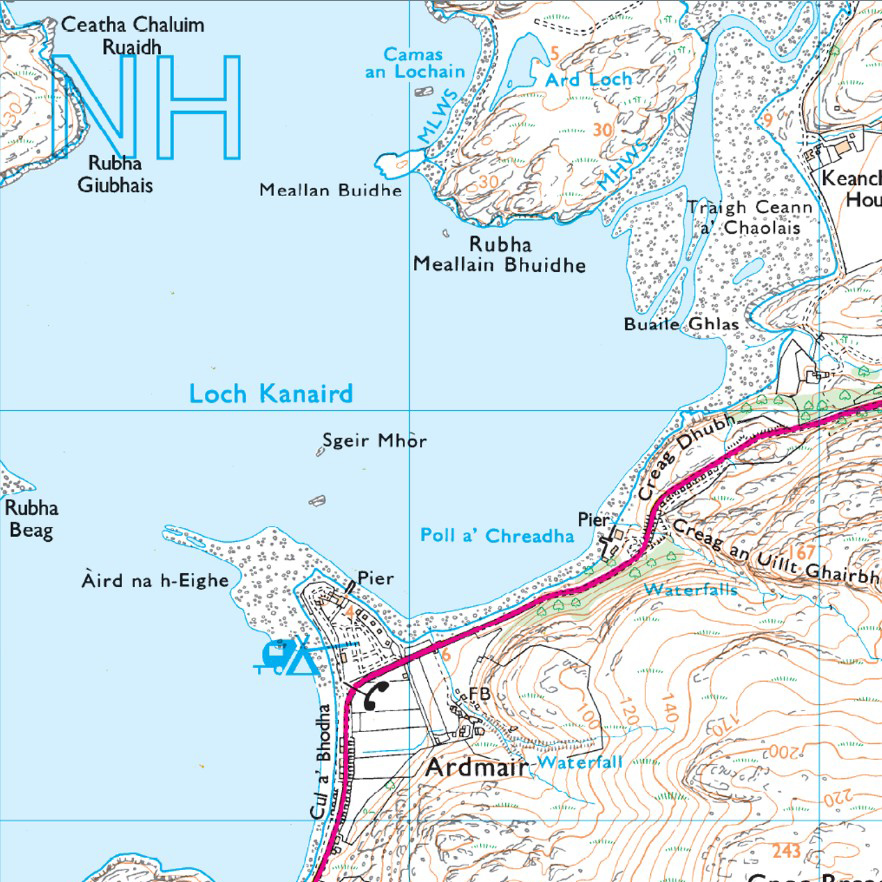

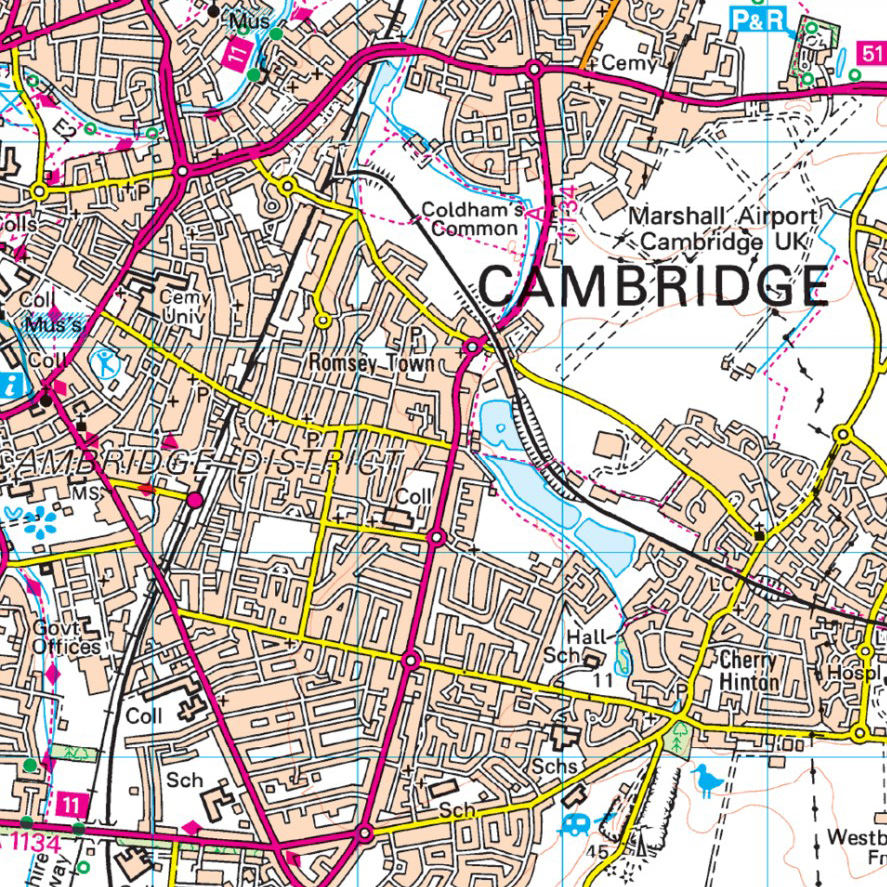

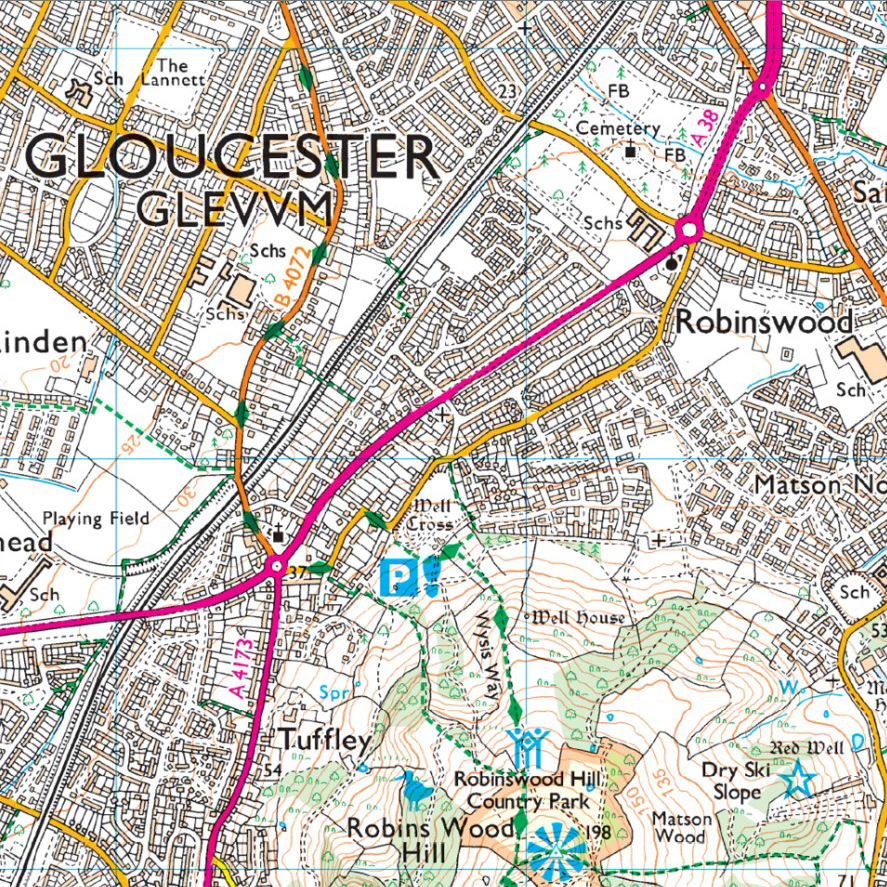

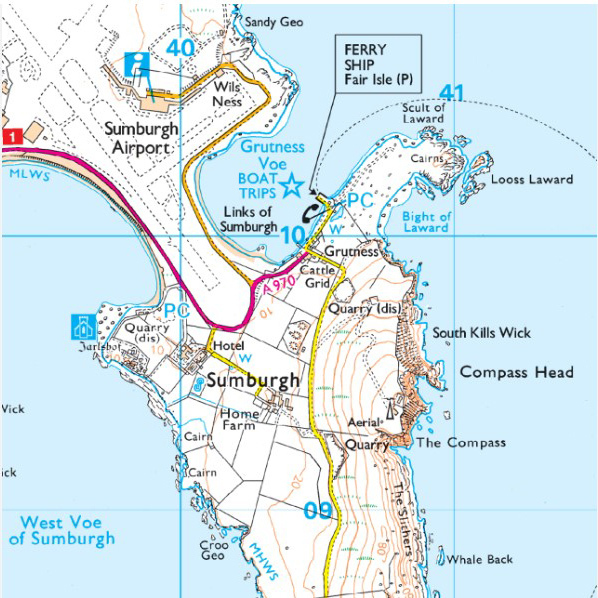

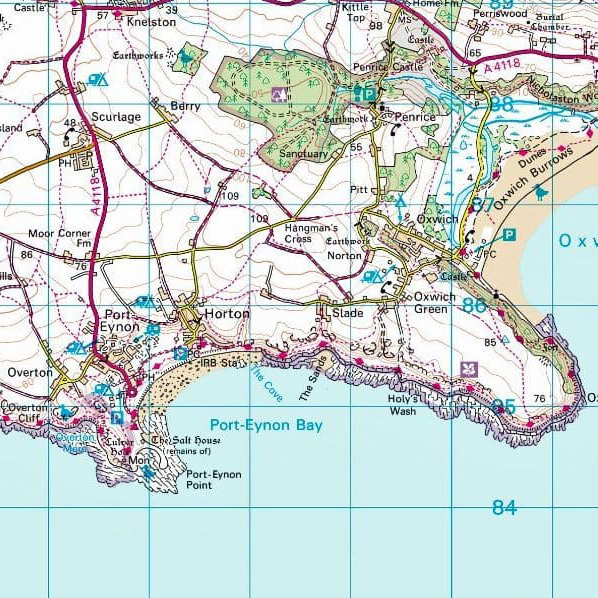

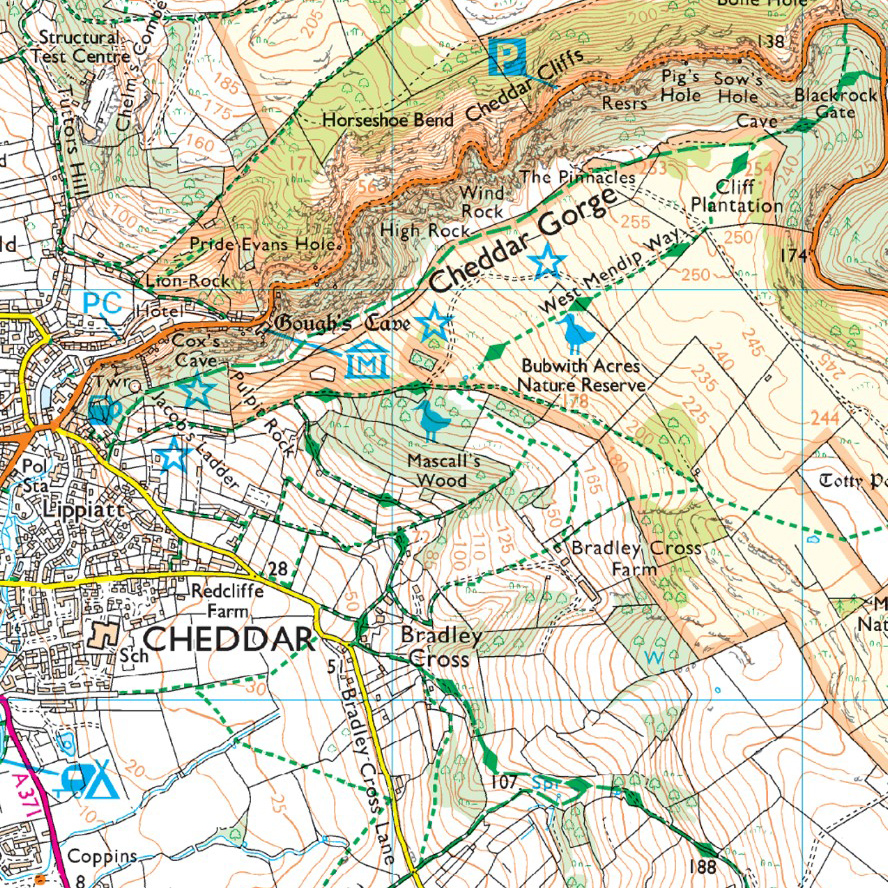

Apart from the book and its cover, I took inspiration from Ordnance Survey maps (not meaning copying). I've been a huge fan of these maps: they are one of those managing to be insanely precise and visually precious at the same time.

I have an impression that official cartographic materials match their countries’ stereotypes: Swiss maps are dramatically beautiful and precise; old Soviet maps are brutal, lacking decorations, precise yet shifted - they kinda try to trick you all the time. In the same way, OS maps represent Britain: smooth-coloured, cosy, packed with things and quirks (check out Ordnance Survey puzzles!), with beautiful icons and great typography. And - it might be a common knowledge, but I wasn’t aware of that before doing a small research for this backstory, and it dilutes my naively unsullied image - they appeared as a means to control Scotland (which was also very British):

Interestingly enough its roots began in 1747 when Lieutenant-Colonel David Watson proposed to King George II a survey of the Highlands, as a means of controlling the Scottish clans after the Jacobite rising in 1745.

vintagehikingdepot.com

(Sorry, I'll just leave it here.)

Meanwhile, in the previous Bryson’s book about England, he mentions Ordnance Survey maps:

As a rule, I am not terribly comfortable with any map that doesn’t have a You-Are-Here arrow on it somewhere, but the Ordnance Survey maps are in a league of their own. Coming from a country where mapmakers tend to exclude any landscape feature smaller than, say, Pikes Peak, I am constantly impressed by the richness of detail on the OS 1:25,000 series. They include every wrinkle and divot of the landscape, every barn, milestone, wind pump and tumulus. They distinguish between sand pits and gravel pits and between power lines strung from pylons and power lines strung from poles. This one even included the stone seat on which I sat now. It astounds me to be able to look at a map and know to the square metre where my buttocks are deployed.

Bryson in 'Notes from a Small Island'

I have an impression that official cartographic materials match their countries’ stereotypes: Swiss maps are dramatically beautiful and precise; old Soviet maps are brutal, lacking decorations, precise yet shifted - they kinda try to trick you all the time. In the same way, OS maps represent Britain: smooth-coloured, cosy, packed with things and quirks (check out Ordnance Survey puzzles!), with beautiful icons and great typography. And - it might be a common knowledge, but I wasn’t aware of that before doing a small research for this backstory, and it dilutes my naively unsullied image - they appeared as a means to control Scotland (which was also very British):

Interestingly enough its roots began in 1747 when Lieutenant-Colonel David Watson proposed to King George II a survey of the Highlands, as a means of controlling the Scottish clans after the Jacobite rising in 1745.

vintagehikingdepot.com

(Sorry, I'll just leave it here.)

Meanwhile, in the previous Bryson’s book about England, he mentions Ordnance Survey maps:

As a rule, I am not terribly comfortable with any map that doesn’t have a You-Are-Here arrow on it somewhere, but the Ordnance Survey maps are in a league of their own. Coming from a country where mapmakers tend to exclude any landscape feature smaller than, say, Pikes Peak, I am constantly impressed by the richness of detail on the OS 1:25,000 series. They include every wrinkle and divot of the landscape, every barn, milestone, wind pump and tumulus. They distinguish between sand pits and gravel pits and between power lines strung from pylons and power lines strung from poles. This one even included the stone seat on which I sat now. It astounds me to be able to look at a map and know to the square metre where my buttocks are deployed.

Bryson in 'Notes from a Small Island'

Ordnance

Survey

Survey

sample maps

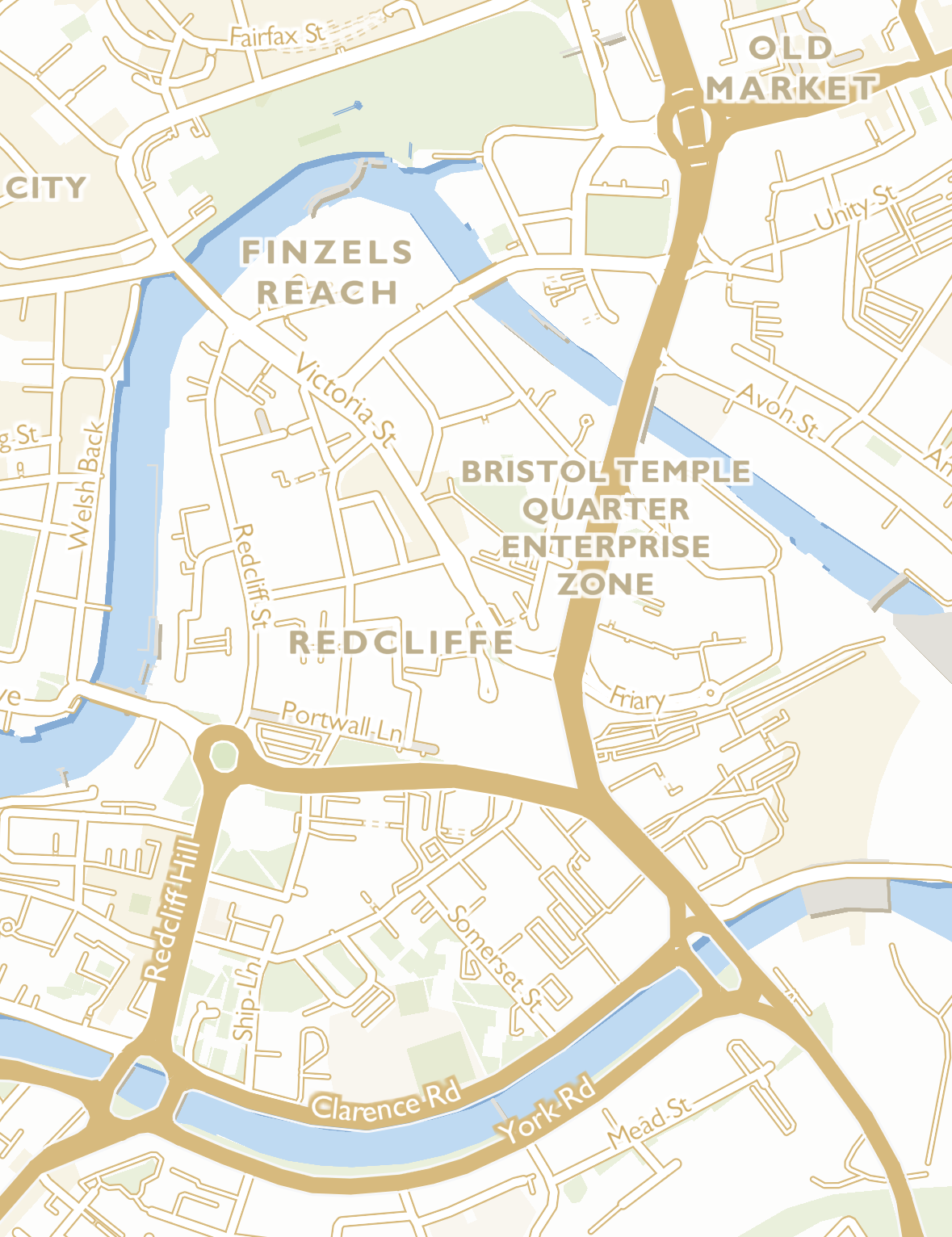

While it’s unfortunately impossible to achieve the same level of detail as OS Maps without equipping a field expedition or conducting an aerial survey, I tried to take inspiration from their neat appearance—bright and delicate at the same time. I’d like to think that the style has diverged far enough from the original to avoid copying, but a few relics remain: for instance, I couldn’t resist keeping these cheerfully pink highways:

You’re welcome to borrow this style, customize it, or use it as-is for your own projects:

Well, to keep rambling about my deliberate (and random) design choices, I should’ve made notes along the way—but I didn’t. Probably for the best, since now this written ramble won’t drag on for ages (or pages).

Instead, let’s browse the map:

Instead, let’s browse the map: